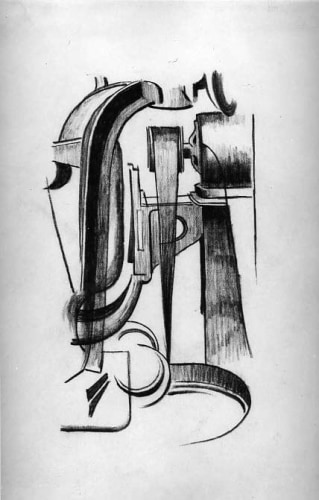

Morton Schamberg

Untitled, ca. 1916

Morton Schamberg (1881 – 1918)

The tragedy of Morton Schamberg’s early death at the age of 37, succumbing to the influenza pandemic, has often overshadowed discussions of his artwork. In a posthumous exhibition of the artist’s work in 1919, the art historian Walter Pach looks beyond the artist’s biography to the works themselves as testimonies of an already successful career: “the pictures before us are a record of achievement. They add something to the world’s sources of thought and happiness, and so, from one standpoint, they pass from the category of the experimental into that of the creative, the definitive.”(1) Indeed, Schamberg’s work exerted an important influence on the early history of American vanguard art, fusing inspirations from a variety of sources into the evolution of a distinct artistic style.

Born in Philadelphia on October 15, 1881, Schamberg was the youngest of four children. He grew up in a household of relatives on Broad Street following his mother’s early death. From 1899 to 1903 he attended the University of Pennsylvania, graduating as a Bachelor of Architecture. Schamberg entered the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1903, remaining there until 1906. He formed a close friendship with Charles Sheeler–both coming to the attention of William Merritt Chase, one of their instructors–and they were among his student group to join up for summer tours to Europe from 1902 to 1904 to study the old masters. In 1906 Schamberg departed for Paris, and it was during this time that he absorbed the European vanguard developments.

The artist’s landscape paintings, in particular, exhibit hallmarks of his early style: loose painterly brushwork, a vivid explosion of color, rhythmic composition, and a break away from naturalism. Having studied under William Merritt Chase at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Schamberg and his friend and fellow student Charles Sheeler traveled to Europe in an exploration of Old Masters and avant-garde developments. France, especially, captivated the young artist, who was inspired by Paul Cézanne’s structured compositions, Vincent Van Gogh’s energetic brushstrokes, and the Fauves’ experimental and non-naturalist use of color.

After returning stateside, the artist and his friend Sheeler rented a house in rural Doylestown to paint on weekends; they often took their bucolic setting as the subject for paintings, and produced numerous meditations on the theme. During this period, Schamberg’s paintings were beginning to attract attention: he had a solo exhibition at the McClees Gallery, Philadelphia, and was receiving local press. In 1913, Arthur B. Davies invited the artist to contribute five paintings to the Armory Show. Following his participation in the landmark exhibition, he exhibited in a group show at the Montross Gallery in New York. A vocal proponent of avant-garde aesthetics, Schamberg persuaded gallery owner James McClees to exhibit a group of pictures from the Armory Show in “Philadelphia’s First Exhibition of Advanced Modern Art—”a courageous act in view of McClees’ friendship with William Merritt Chase and Chase’s antipathy to this controversial art. (Following Sheeler’s and Schamberg’s participation in the Armory Show, Chase never spoke to his former students again.)

Influenced by Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia, whose acquaintance he made at the Arensberg salon in New York in 1916, Schamberg turned to the machine for inspiration, predating Sheeler’s Precisionist works by five years. The artist was also a pioneer in photography; although he and Sheeler had initially adopted the medium as a source of income, Schamberg produced some of the earliest photographs of the modern industrial city, and was one of the first to use a silvered background to reflect muted light.

Unlike many artists who die young, Schamberg’s works were collected during his lifetime. The prescient patrons of American modernism, Walter Arensberg and John Quinn, both acquired Schamberg’s paintings for their collections.

1. Walter Pach, “The Schamberg Exhibition,” “The Dial 66″ (17 May 1919): 505, cited in William C. Agee, “Morton Livingston Schamberg: Color and Evolution of his Paintings” (Washington, D.C.: Board of the Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 1984), n.p.

Biography from the Archives of AskART